I heard these sounds in February.

Mausoleum acoustics, tuned air.

A strained nothing sound. Air thin choral resonances.

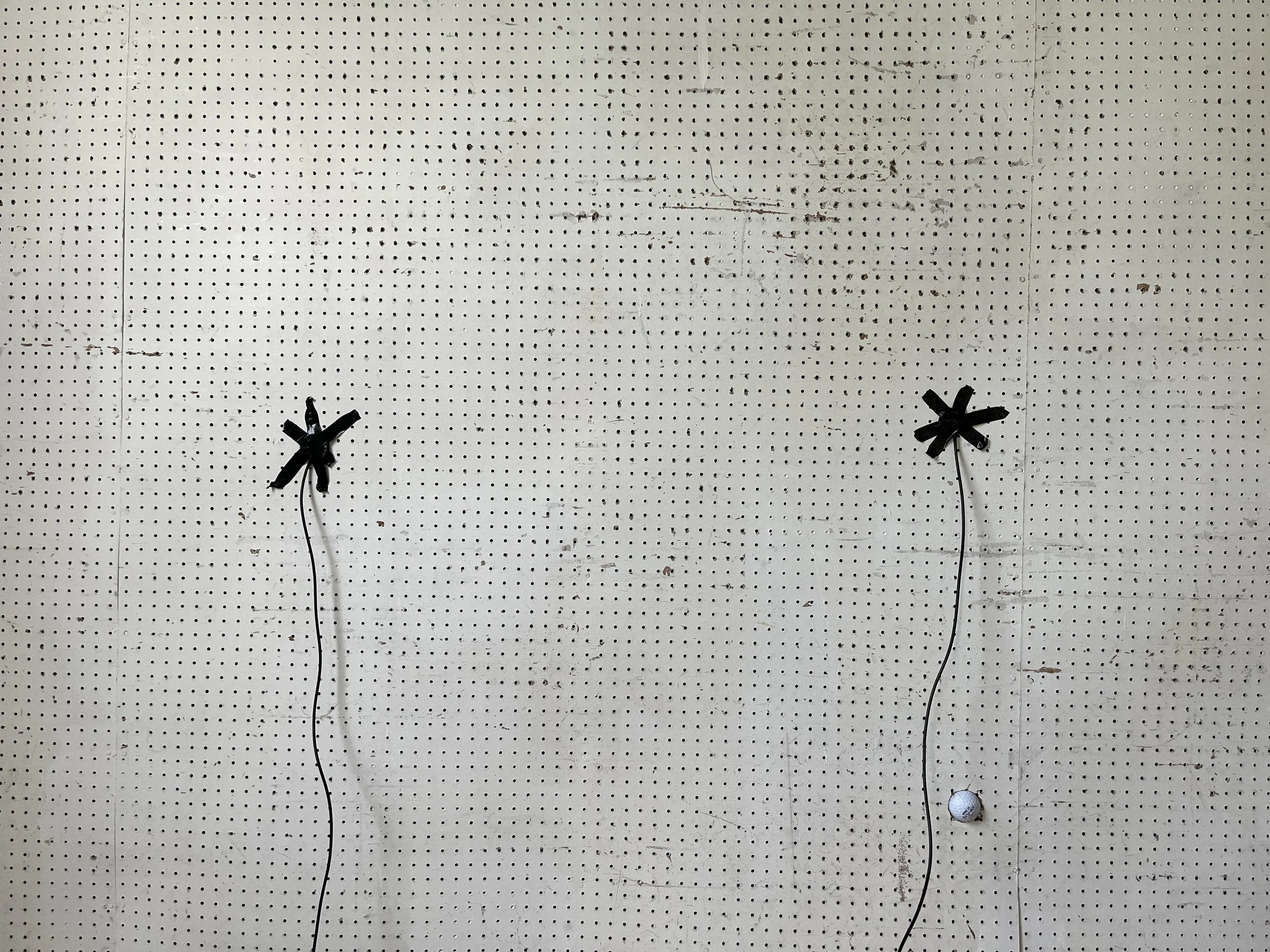

Leaning in between acoustic screens.

I step through the curtain, drop my self consciousness and sing. I find harmony with AI, enjoying the secluded, private space to share my voice. I wonder if I’m singing with another human, unseen in the booth opposite me.

I face a wall with my back to the speakers.

Ponies squelch through mud in Hyde Park. The ground I’m walking on is wet. Every footstep slick and glistening. I look up just as a formation of croaking geese fly towards me, passing just over my head. I hear fluttering details of feathers beating.

A voice against a backdrop of cicada’s, wavering tones and ambience, plays from a small speaker cone embedded in an old, brown wooden box. The sound waves leave that box, pass over a floating wooden approximation of a toilet bowl and cistern before activating the wide gallery acoustics.

A soft motorised rhythm pulses, then a hum and a click before that original pulse takes on a ticking higher note that ripples away from me.

Variations of the above sequence surround me.

Distant, faint rising and falling pitch like an air raid klaxon.

Occasionally a squeak ignites the room like a sneaker on a basketball court.

The wooden box voice drifts through to here.

Read More